In autumn 2024, Wolt removed exclusivity and price parity clauses from its contracts with restaurants after the Finnish Competition and Consumer Authority (FCCA) had examined the legality of these clauses and their effects on the market. Following these changes, the FCCA closed its investigation into Wolt. The Authority has nevertheless continued to monitor market developments. In this blog post, we present preliminary findings from our assessment of how the contractual changes have affected the market for food delivery platforms.

Objectives of the contractual changes

The FCCA’s investigation was motivated by concerns that Wolt’s exclusivity agreements could lead to the market tipping in Wolt’s favour. The clauses prevented restaurants from multihoming, that is, from operating on more than one platform simultaneously. As restaurants increasingly concentrated on Wolt’s platform, network effects emerged. These effects were further reinforced by consumers’ tendency to shift not only purchases from exclusive restaurants, but also other orders, to Wolt. (More on network effects in our previous blog post in Finnish)

As consumers moved to Wolt, restaurants that hadn’t entered into exclusivity agreements also increasingly chose to operate solely on Wolt’s platform. This raised the risk that, by tying restaurants to its platform, Wolt could foreclose Foodora from the market and deter entry by new competitors. By the removal of exclusivity clauses, the FCCA sought to enable restaurant multihoming and to halt the tipping dynamics caused by the contractual terms. Foodora, which was not subject to the Authority’s investigation, has been able to continue entering into exclusivity agreements with restaurants.

Abandoning exclusivity agreements can however also have effects that are unfavorable from a consumer perspective. When signing an exclusivity agreement, restaurant typically loses some customers that it previously reached through the other platform. For this reason, platforms often compensate restaurants for the exclusivity agreements by charging them lower sales commissions. When Wolt discontinued exclusivity agreements, it raised the commissions charged to restaurants. According to economic theory, increases in commissions are at least partly passed on to consumer prices. The FCCA nevertheless assessed that, in the long run, the benefits of preserving competition would outweigh the price-reducing effect of lower commissions.

Another key concern underlying the FCCA’s investigation was the effect of Wolt’s price parity clause on restaurant pricing. Under this clause, the prices of products sold on Wolt’s platform could not exceed the prices charged by the restaurant in its own sales channels. Such a so-called narrow parity clause eliminates price competition between the platform and the restaurant’s own channels. Because restaurants cannot compete against the platform by offering lower prices elsewhere, the platform can increase the commission it charges without fear that restaurants would respond by lowering prices in their own channels and thereby diverting sales away from the platform. Restaurants, in turn, are forced either to pass the higher commission on to prices, including prices charged in the dining room, or to accept lower margins. As a result, the overall price level of restaurants may increase.

The objective of removing the parity clause was therefore to allow restaurants to charge higher prices for dishes sold on Wolt than for those sold in the dining room. Foodora also applied a parity clause. However, Foodora’s clause applied only to restaurants’ own online sales channels, whose role in Finland is relatively limited.

Scope of the analysis

Economic theory provides useful guidance on the likely effects of Wolt’s contractual changes. However, food ordering and delivery markets do not map neatly onto standard theoretical models. For this reason, our analysis focused on a limited set of core questions that allow us to assess whether the removal of Wolt’s contractual clauses has produced the intended outcomes.

- Has the restaurant multihoming increased?

- How have the choices of singlehoming restaurants changed?

- Has Foodora stopped losing market share?

- Did the previously exclusive restaurants raise prices?

- Have the restaurants raised prices on Wolt compared to the prices in the restaurants?

Multihoming among restaurants increased

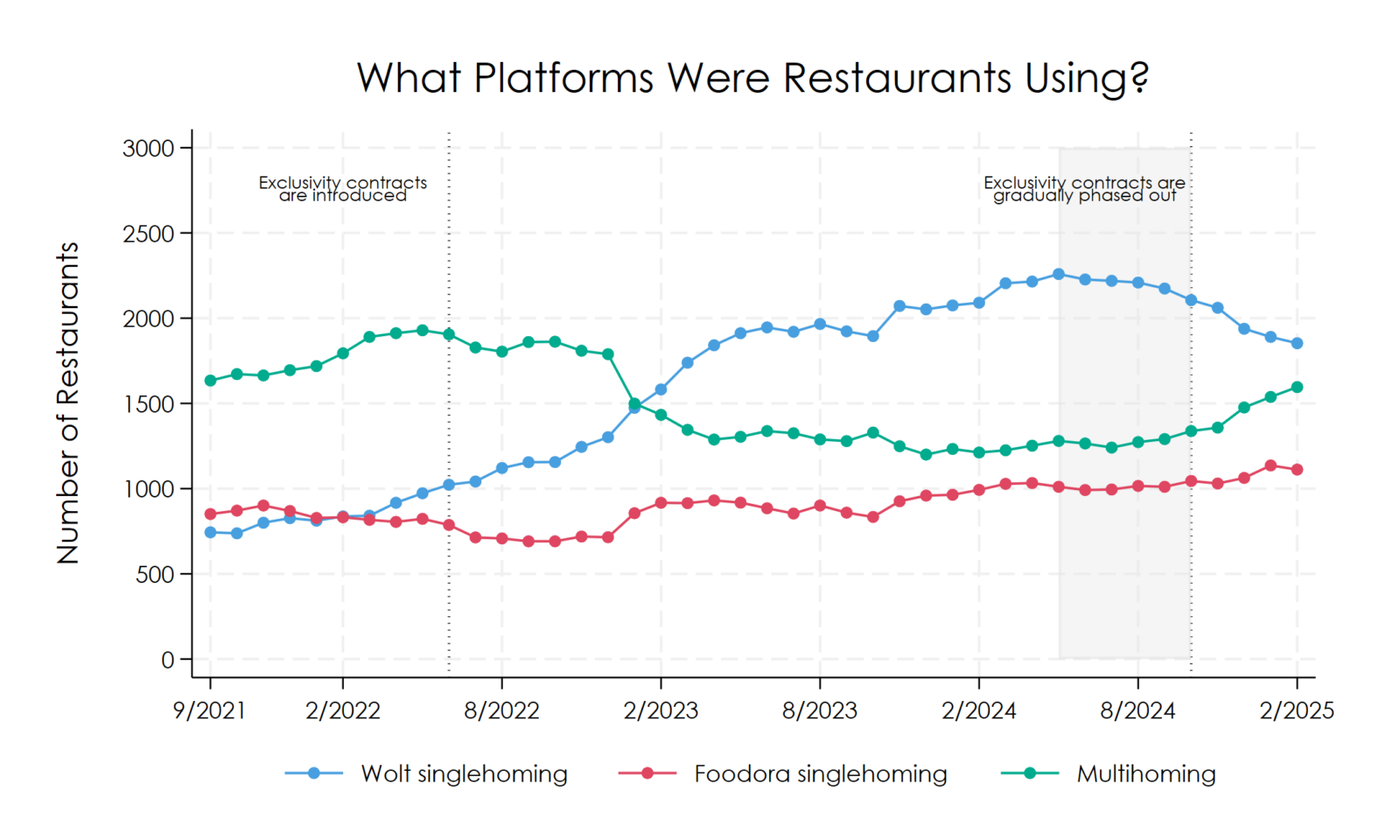

To answer the first question, we classified all restaurants operating on the platforms as either singlehoming or multihoming and examined how the number of each evolved over time. Singlehoming restaurants operate exclusively on either Wolt or Foodora, while multihoming restaurants operate on both platforms. The figure below illustrates how singlehoming on Wolt increased rapidly in 2022–2023, when the use of exclusivity agreements expanded the most. The peak in singlehoming and the lowest level of multihoming occurred in spring 2024, when the FCCA informed Wolt of its preliminary assessment. After this point, the number of multihoming restaurants began to increase, with growth accelerating further in autumn 2024, when Wolt discontinued the use of all exclusivity agreements. By February 2025, the number of multihoming restaurants had increased by approximately 25 per cent compared to spring 2024. Over the same period, the number of restaurants operating only on Wolt began to decline.

Part of this change is directly attributable to former Wolt-exclusive restaurants, which started using Foodora once their exclusivity agreements ended. However, our analysis indicates that multihoming increased and Wolt-only singlehoming declined among other restaurants as well. This may be explained by network effects typical to platform markets. Many of the exclusive restaurants were well-known restaurants and chains. When these restaurants began operating on Foodora as well, the platform became more attractive from the consumers’ perspective. The strengthening of restaurant supply and the resulting increase in the number of consumers on the platform may, in turn, have encouraged additional restaurants to start using Foodora.

The platforms’ market shares are confidential, which is why we cannot report their precise development. As noted in the FCCA’s decision, however, Wolt gained approximately 5–10 percentage points of market share from Foodora during the period when exclusivity agreements were in use. After the agreements ended, this trend reversed and Foodora’s market share began to increase slightly. The pace of this increase from October 2024 to the end of February 2025 was nevertheless slower than Wolt’s earlier rate of growth.

From the perspective of multihoming and market shares, the removal of exclusivity clauses therefore appears to have had the intended effect. Another, potentially even more significant development is the entry of new platforms into the market. According to preliminary reports, Uber Eats may be launching operations in Finland. Uber Eats is one of the world’s leading food ordering and delivery platforms and operates at a comparable scale to the corporate groups behind Wolt (DoorDash) and Foodora (Delivery Hero). Although the entry of competing platforms cannot be directly attributed to the removal of Wolt’s exclusivity clauses, facilitating market entry was one of the objectives identified by the FCCA in abolishing these contractual terms.

Higher commissions appear to have been passed on to prices

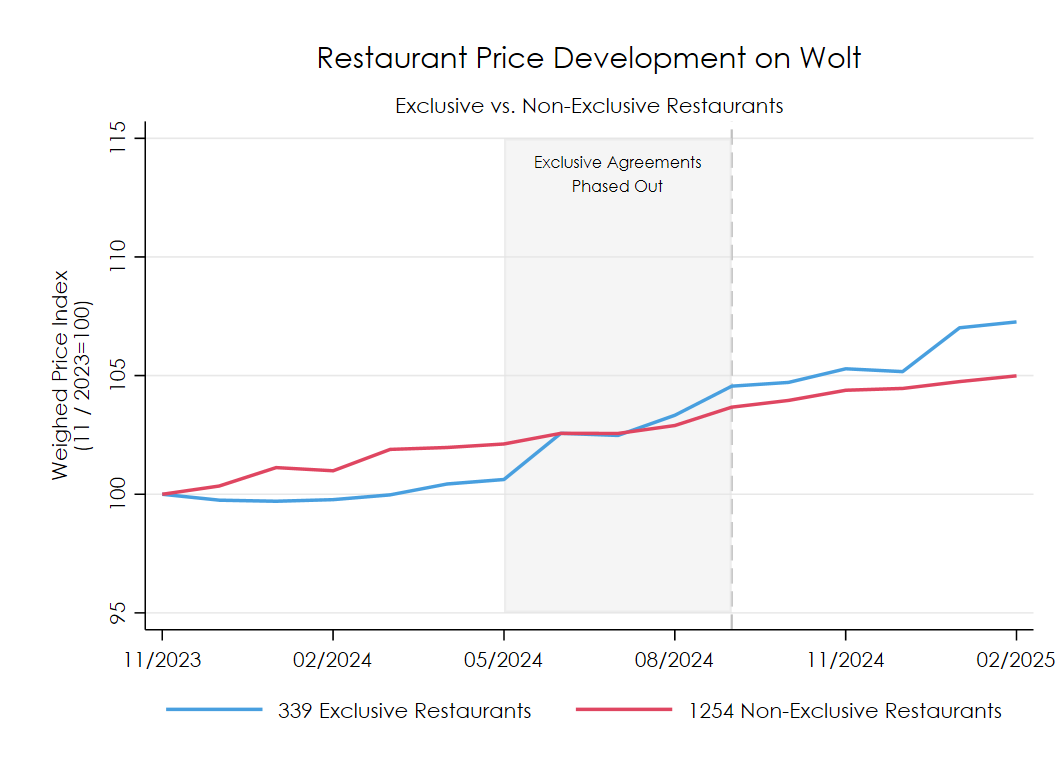

The price effects of the termination of Wolt’s exclusivity agreements were examined by analyzing changes in the list prices of each restaurant’s five best-selling products on Wolt. The figure below compares restaurants that had an exclusivity agreement with Wolt in force at least between November 2023 and May 2024 with restaurants that did not have an exclusivity agreement at any point during the observation period. For both groups, a sales-weighted price index was constructed, normalized to a value of 100 at the beginning of the period.

The figure shows that, prior to the termination of exclusivity agreements, the price level of exclusive restaurants developed slower than that of other restaurants. One possible explanation is that restaurants benefiting from lower commission rates did not actively reduce prices but instead refrained from implementing customary price increases. After the exclusivity agreements ended, however, prices at former exclusive restaurants increased significantly faster than prices at other restaurants. Between May and September 2024, prices at former exclusive restaurants rose by approximately 2.4 percentage points more than prices at other restaurants. The gradual changes observed in the price index of former exclusive restaurants are largely explained by chain pricing practices and the phased termination of agreements. Overall, the price developments are consistent with the hypothesis outlined above, according to which the increase in commission levels following the termination of exclusivity agreements was at least partly passed on to restaurant prices.

Restaurant prices are often lower than platform prices

To examine the effects of the price parity clause, we conducted a survey of restaurants. The primary purpose of the survey was to collect data on pricing for on-premises dining, as the data obtained by the Authority from the platforms cover only orders placed through those platforms. The survey was sent to 2,300 restaurants, and 473 usable responses were received.

The main objective of the analysis was to assess whether restaurants had, following the removal of the parity clause, made use of the freedom to set higher prices on Wolt than in the restaurant. In addition to examining the current situation, we also sought to determine whether price differentiation had changed over time. A key challenge was that restaurants do not always retain historical price lists. For this reason, we applied alternative approaches to measure the changes.

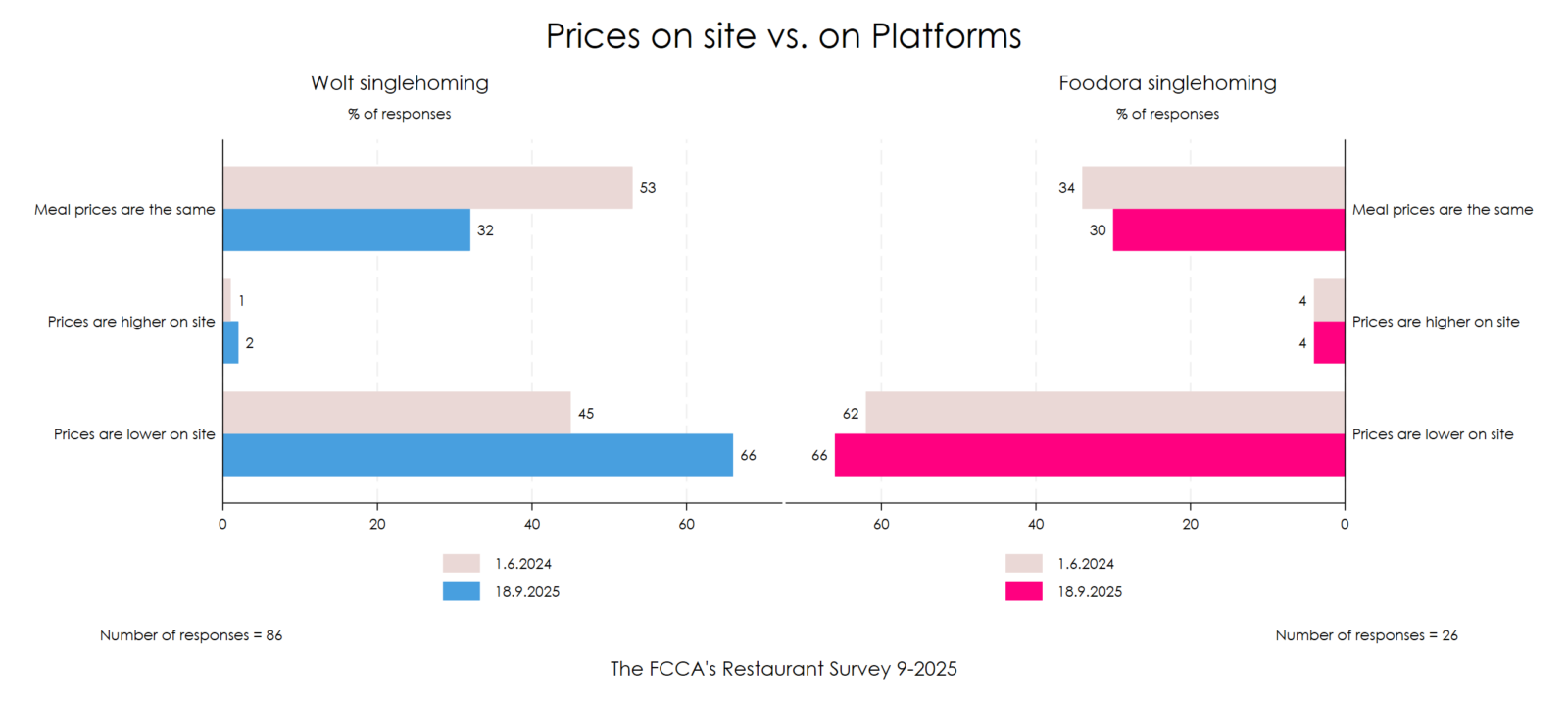

The first approach was to ask restaurants for their own assessment of whether their prices in the dining room were lower, higher or the same as their prices on Wolt on 1 June 2024 (i.e. before the contractual changes) and on 18 September 2025 (i.e. after the changes). The same question was also asked with respect to Foodora, of the restaurants that operated on Foodora.

As described above, our hypothesis was that the change to Wolt’s parity clause would be most clearly reflected in higher platform prices among restaurants that operate exclusively on Wolt. Since Foodora did not have a corresponding contractual provision, no similar change should be observed among restaurants using only Foodora. Our findings support these hypotheses. Based on the figure below, fewer than half of Wolt singlehoming restaurants priced their dishes lower in the restaurant than on the platform in summer 2024. By September 2025, this share had increased to around two thirds. Among Foodora singlehoming restaurants, by contrast, two thirds had already charged lower prices in the restaurant in summer 2024, and this proportion did not change significantly. In other words, following the removal of the parity clause, price differentiation between the restaurant and the platform among restaurants using only Wolt has begun to resemble the pricing behaviour of restaurants operating only on Foodora.

The results also show that not all restaurants complied with Wolt’s parity clause even while it was in force. At the same time, they indicate that not all restaurants are making use of the opportunity to differentiate prices. Restaurants operating on both platforms changed their behaviour less than the Wolt singlehoming restaurants shown in the figure. Interpreting this finding requires further analysis. In addition to price differentiation, we asked restaurants whether they had adjusted portion sizes or the breadth of their menus following the removal of the contractual clauses. Based on the survey responses, no such effects were identified.

In addition to questions based on restaurants’ own assessments, we sought to measure price differentiation by requesting menus that restaurants had used on 1 June 2024 and 28 February 2025. These menus were combined with microdata obtained from the platforms, enabling a precise comparison between restaurants’ own prices and platform prices. Unfortunately, the size of the resulting dataset was limited, as only a relatively small number of restaurants were able to provide discontinued menus. Based on this comparison, restaurants differentiated prices between the dining room and the platform both before and after Wolt’s contractual changes. Unlike the survey-based responses, however, the menu data did not reveal a significant change in the extent of price differentiation.

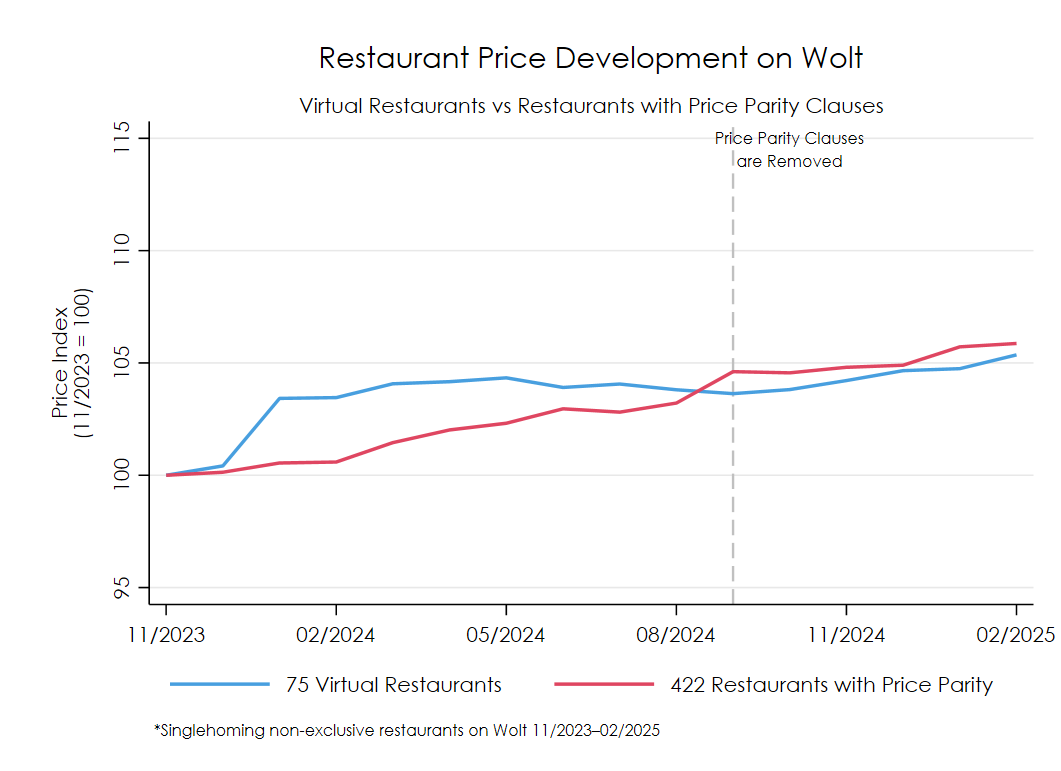

The impact of removing the parity clause on prices was also examined by comparing two groups of restaurants on Wolt. The first group consisted of virtual restaurants that sell food exclusively through platforms and were therefore never subject to the parity clause. The second group consisted of restaurants subject to the parity clause, in practice all other restaurants operating only on Wolt. Restaurants bound by exclusivity clauses were excluded from the second group to ensure that the effects of removing exclusivity were not confounded with those of removing the parity clause. The comparison was based on the assumption that, absent the removal of the parity clause, price developments at parity restaurants would have broadly mirrored those observed for virtual restaurants.

In practice, however, price developments differed somewhat between the two groups even before the parity clause was removed, which weakens the basis for comparison. When the parity clause was removed in September 2024, prices at parity restaurants show a small increase of around 2 per cent that is not observed in the comparison group. Taken together with restaurants’ own assessments, this provides indications that removing the parity clause has likely had some effect on restaurant pricing on Wolt’s platform. However, a purely descriptive comparison of prices does not demonstrate that the observed change is attributable specifically to the parity clause, and overall, the effect appears limited.

The removal of the parity clause may also have a positive effect on competition between platforms. Platforms compete with one another primarily through their commission levels. Typically, when a platform lowers its commission, the restaurant’s marginal cost decreases, giving it an incentive to lower its prices on the platform as well. The resulting increase in restaurant sales also benefits the platform.

Food delivery markets, however, are characterized by the fact that a portion of restaurant demand comes from customers who prefer to dine on the premises. If a platform applies a narrow parity clause, a reduction in commissions would require the restaurant to lower prices for this group of customers as well. This benefits only those customers, not the platform, which weakens the platform’s incentive to compete on commission levels.

Pro-competitive effects take time to materialise

Overall, our analysis suggests that the effects observed during the first four months following the removal of Wolt’s contractual clauses were broadly in line with expectations. At least customers who dine in restaurants or use restaurants’ other own sales channels appear to have benefited from the change to the parity clause. Based on our restaurant survey, approximately 75 per cent of a typical restaurant’s sales still come from these channels, which means that the overall consumer benefit may be substantial. At the same time, prices on Wolt’s platform at former exclusive restaurants have increased as a result of higher commission levels.

From the consumer perspective, the most beneficial effects are likely to materialise only over a longer period of time. Increased multihoming, potential market entry by new competitors, and the pro-competitive effects of removing the parity clause should place downward pressure on platform commission levels, thereby benefiting all platform users.

Wolt’s contractual changes are also of interest from a broader competition law perspective. Ex post assessment of the effects of these changes enhances understanding of how contractual terms used by platforms affect market outcomes and firm behaviour. Previous empirical research on platform parity and exclusivity clauses has been relatively limited and has focused largely on hotel markets. Research on food ordering and delivery platforms is considerably more limited, particularly with respect to the effects of exclusivity agreements, for which empirical evidence remains scarce.

The issue is timely, as many countries and authorities are currently examining the functioning of food ordering and delivery platform markets and the contractual practices of the platforms. Our intention is to publish a more extensive research paper next year based on the analyses described in this blog post.

Thomas Gräsbeck, Miika Heinonen, Olli Kauppi and Janna Öberg

Economists, Competition Division, Finnish Competition and Consumer Authority